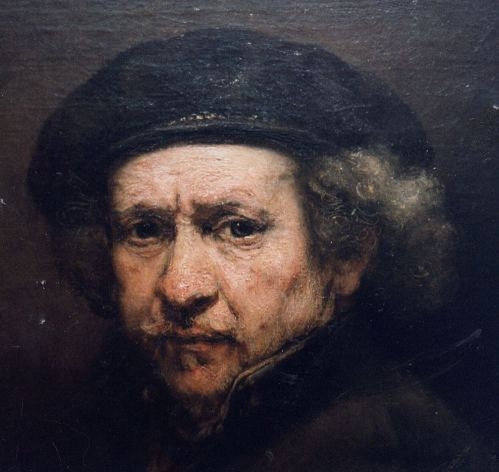

My Attempt at a Rembrandt self portrait Part 2

Here is a detail showing the paint topography of the mask before final glazing and finishing: The whole thing is 'dead' and rough when viewed in natural daylight. Prognosis? Glazing and some scumbling will both colorize and soften the harsh topography.

There are a certain few parts of the Rembrandt's "mask" showing over-painting with stringy, what seems to be a pure, untempered, white lead pink. What I mean is, such characteristics could not be easily made with shorter tempered paint, unless that was thinned more. Again, if R did use such simple paint� and I see no real reason to doubt it � odds are high he at least added a drying agent� such as the old Olio Cotto (lead paste).

An example of such stringy (but drying!) paint is a clever and very informative jot at the bridge of the nose-- made best with the tip of a palette knife-- which left a long tail or peak as it was withdrawn. As the blurry image close-up below shows, as the knife withdrew, this peak folded over itself and collapsed with gravity. This jot is rather amazing to find as it is totally indicative of the very cavalier attitude on the part of the painter, who seemingly didn't care a whit for an overall smooth-approach to reproducing his own features; and, contrarily, desiring as much ruggedness within his creation as his tools and materials could muster. We can assume this rugged and outstanding jot was not alone as the highest elevation of R's portrait; indeed, there must have been other elevated areas to peaceably co-exist along with the jot. BTW, this particular knife-applied jot composed of a thinner paint ( could have been either tempered or un-tempered) was most likely made during the dead coloring stage. I now show these following knife-jotting images:

Here is a jot made by the knife leaving the paint surface. The paint is thick enough that the peak does not collapse. The peak forms as the gooey paint tries to keep hold of the knife:

Here is R's jot:

Here is a blurry full shot of the "jot" on R's upper nose-bridge (see above image) and likely made with the knife, its peak fallen downwards and forever pointing to the floor of R's studio (meaning, simply, he was painting this stage of the portrait while that was positioned vertical on the easel ):

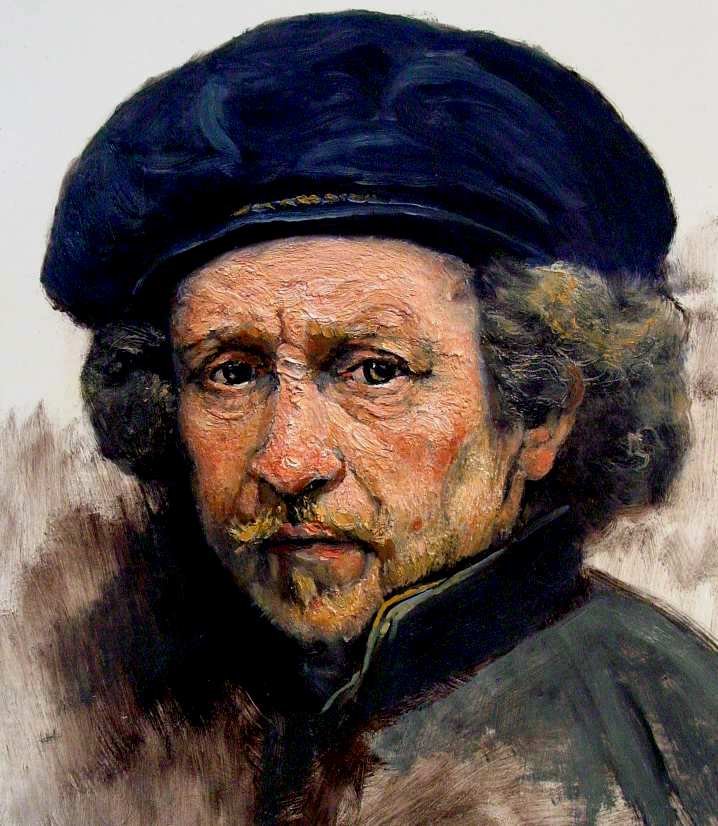

Stage 4) Final Coloring. After skipping two more days to encourage at least surface-drying of the thickly applied paint (and making a few more additions), I mixed up some painting jelly and made very weak glazes and scumbles by touching into the jelly tiny speck-amounts of VR, YO, as well as shadow glazes made from these same colors plus Ultramarine blue. These shadows I carefully washed very faintly over the hair and hairline areas (as already noted above). Essentially, at this final stage, I was using the faintly tinted jelly to varnish my work. The shadows were brushed in first. A Venetian red glaze was given to the cheek; also the nose and the obvious highlight applied with a small thin brush loaded with white lead was placed at near center of R's bulbous sniffer. Some faint YO with VR oranges were washed in everywhere needed. I also used some vermillion red mixed with white to better colorize the mouth. Some soft white lead was made-up and a good many thin strokes of flesh-colored paint were applied using the liner. These occurred especially around the eyes, softening the harshness before seen. There is a bluish-green blood vein very subtley glazed into R's upper temple, this done using a thin sable. Not much painting was done this final day, really, for the work seemed mostly according to my remembrance. Few mixed tones were used during the construction of the mask. The use of handground paint negates a lot of the troubles found when attempting to blend modern tube colors together.

The final glazing/scumbling brought the various colors together and presented a pleasing and proper appearance. [The use of many initially-mixed tints is taught today for portrait painting. I will again say I believe this was un-necessary to the olden painters. Certainly, alla prima portraiture would require the mixing of more tints to begin with, but the clever painter using few mixes will apply some basic and purer tones quickly and surely; and then produce the differing requisite tones by brushing in slight amounts of the parent color as well as a titch of, say, white, black, blue, and red /yellow to get much the proper effect-- the mixing thus being done on the face, not the palette....a bit easier with the handmade stuff rubbed up fresh and tempered to suit.

Below is the finished work photographed after all was dry. Due to the use of a rich glazing and scumbling medium, the work mostly dried with a pleasant gloss. A bit of sinking occured here and there where the glazing sank into the thick underpaint of the mask. This is a set-up for possible later fissuring. No problem, though; another scrub-on of the painting jelly in the sunken areas resulted in a perfect shine and lasting protection.

Rembrandt self portrait copy by James C. Groves

I realize this appears quite a bit more colorful than that darkly-recorded close-up of R's portrait posted at the beginning of this report; unfortunately, that dark image was the best close-up I had available. For those who might wish to see what this final colorful creation becomes when I use an image-editing program to darken the finished portrait and diminish the colors, click

here.