Groves' Amber Gelling Varnish ( for making painting jelly) 80 mil. glass bottle

Gelling Oil is a tough resinous varnish I developed to recreate the stunning surface and optical qualities of the 15th and 16th Century Flemish and Dutch painters. When this varnish is mixed with any regular painting oil, a painting 'jelly' is created. [Update 2006: Our Amber Gelling Oil now comes in the bottle version; and is concentrated to produce up to twice as much painting jelly as the tubed version; plus, as with our Gelling Copal Varnish and our Sandarac Gel Varnish, the gelation effect is now instant upon mixture with the oil. Be aware, for those who have reactions to turpentine spirit, this bottled version does contain that solvent.]

Historical evidence and considerations

Some writings suggest the Van Eycks invented oil painting. Not so, for anyone poring over the old manuscripts and other texts will easily see that oil painting was known to the very ancients. Much more likely is the notion the brothers VE perfected a method of painting that allowed it to rise above its clumsy nature, to a level that finally surpassed the egg tempera methodology-- which, as the 14th Century Cennini wrote, was previously the ages-old favorite manner of achieving realistic depiction.

The appearance of the Van Eycks work is rather stunning; and many historical oil painting experts have particularly focused research and guesswork upon the exact medium-means of the well-known brothers.

As one noteable example, A.P.Laurie was rather convinced the secret lay with stand oil, or a boiled oil with similar character. As somewhat proof for his 'standoil' contention, Laurie employed a sign painter to reproduce the famous Van Eyck signature on the Arnolfini Portrait-- and he achieved good success. [Note: while it is possible VE used a sign painter's brush, still, I look at his clever signature on that famous portrait and see only the work of a common caligraphy pen charged with a slightly resinous oil-and-carbon-pigment "ink". BTW, according to his last book, "The Painters Methods and Materials", 1960, professor Laurie thought it likely Rembrandt, and many other old masters, also used thickened oil like standoil. Those of us who make our own paint will see the error in this possibility, for you see, a simple drop of standoil will instantly reduce our lovely stiff-standing paint to a "melting" enamel-like condition.; and actually using the pure standoil, alone, to rub-up our colors would be even worse. No, the rugged impasto of Rembrandt would not be possible by a standoil route. [Note: late in life, when asked what medium he thought the VE's might have used, Laurie replied that their wonder medium may well have been based on pine resin.]

Many painters today might agree with Laurie's 'standoil' point-of-view, for the surface of VE's works do bear a resemblance to having been painted with a polymerized oil, such as standoil. But there are various other means to achieving an enamel-like appearance, such as the use of slightly-aged paint (raw oil and pigment paint rubbed-up fresh in the evening and then utilized the following morning). Another method would be to simply add some coniferous balsam to the freshly-rubbed-up paint. By this balsam-route, a certain melting/difffusing occurs as the paint dries ; it levels out, forming a smooth surface. The problem with this second balsam method is the paint is somewhat weak to future varnish-removal ; plus, while painting in layers, further superimpositions with the same balsam-bearing medium can dissolve the underlying and seemingly dried layers.

Another obvious strike against use of standoil-like boiled or sun-thickened oils comes quite directly from the actual history preceeding the Van Eyck-ian discovery. As it happened, the Italian Cenino Cennini wrote a now famous handbook ("Il Libro Dell' Arte") in the late 1300's wherein he mentioned that the best manner of painting in oils was to be had by use of the boiled or sun-thickened oils. Some might think this positive evidence for Van Eyck's later 1400's use of such thickened oils; however, the wizened Cennini plainly states that egg tempera is the better and more efficient method for depicting realism. He tells us the thickened-oil painting system is better suited for walls and doors. Thus, his own experience with the boiled and sunned oils show only what those of us who have tried them have found; that they represent a clumsy methodology with no outstanding advantages over egg tempera .

And so, whatever it was that the brothers Van Eyck found, it was not likely the use of boiled or sun-thickened oils, alone, with the pigments; instead, that route was already well-known ....and espoused as the finer oil painting method-- but not a method that would detract from the comparative excellence and ease found with the popular tempera easel/panel painting. [Note: the Italian 1400's painter, Antonella Da Messina, seeing a Van Eyck work for the first time, was bewildered and taken aback by its superior attributes. I think it might be postulated that Messina would have been well-aware of and experienced with egg tempera and the thickened-oils approach to oil painting.]

The possibility that the VE's used natural resins cooked into oils has also been advanced. Certain resin-additions to oil paint can immitate the olden paint and so this theory has been promoted by numerous paint-detectives down through time. One proponent of this thinking was a Dr. Coremans of Belgium. Compared to Laurie's theory which was based on a trial of actual painting practice, Coreman's theory had what many would regard as a more scientific basis. Dr. Coremans performed micro-chip paint analysis while undertaking restorations of Van Eyck's "Ghent Alterpiece". In defiance of many other theorists, Coreman's maintained there was no use of egg tempera by the legendary Dutch painter. Instead, Coremans found the paint contained oil and a substance showing characteristics of natural resins (see, for example, Frederick Taubes' 1953 book "The Mastery of Oil Painting").

Since Coremans' investigation, which, of course, was performed using the best analysis techniques of the mid 20th Century, many other 'scientific' painting experts have added their findings to the realm. Some of the newest investigators say the VE's paint chips test positive for some protein -- thus, in disagreement with Coremans, they maintain the technique involved an egg-type ingredient.

I am sorry to say that "Modern Science" will never get to the bottom of VE's technique. Why? Because Modern Science is ever evolving, with newer testing procedures (and researchers) supplanting the old. Though we today may think our modern science knows all, we are just as delusional as those who inhabited this planet 100 years ago-- unwitting souls who felt and thought the very same about 'their' modern science ; believe me when I say, the modern science of 50 years from now will consider our time little more than the dark ages (and, in kind and proudly believing 'their' age is the age of truth, they will also be mistaken).

I must think the better means to rediscovering VE's technique will always be to actually attempt to reproduce it ... and modern science is not capable of that route. Only talented painters will perform and produce in such realm. Unfortunately, painters are artists; and artists --like scientists -- can rarely get along or agree on much of anything.

The Van Eyck approach-- something quite new...

Regarding Van Eyck and his methodology, as with every other old master investigated down through the years, confusion is the proper descriptive word as we are now, today, even more perplexed by all the differing points of view.

What is so great about VE's works? Simply this: Certain of these works seem to represent the perfect oil painting technique coupled with the perfect paint. True, Van Eyck's subject matter is not perfect in a reality-wise manner. No. Personally speaking, I would have to say it is this olden painter's surface quality above all else that I am most struck by. Again, his technique of paint application, the color breadth, the optical clarity of the whole-- all is so perfectly done. Of the various time-periods throughout oil painting history, it is this particular early Renaissance time period's productions that entice me to possibly consider a lost means of paint-making and technique-ability.

Van Eyck's technique was quite different to that manner espoused by his predecessor, Cennino Cennini. Cennini clearly states that each object was to be rendered in paint by mixing and applying three separate color-tints using the thickened oils he mentions. The typical leveling effect of these poly-type oils will produce a smooth enamel-like surface. Now, the optical brightness of such work will come from the use of a white opaque paint-- such as lead white-- being actually mixed with the various colors to lighten them in tone. For instance, if a blue robe is to be painted, the painter need mix a tint matching the color of the highlight (light blue, say, ultramarine blue mixed with some lead white), the general body color (a medium blue), and the shadow color (perhaps the medium blue mixed with black). As such, Cennini is telling us that oil painting is to be done with opaque paint, the brightness of which is dependent upon the color-purity or the amount of white added. In such case, the brightness we see is reflected directly off the color and back to our eyes. I cannot argue against this method, for I have made some very fine detailed work in just such manner; and I see no reason why it should not stand well against time.

However, this use of truly opaque paint is not the method of J.Van Eyck. Nor is his paint enamel-like; this is mostly a delusion. To my eyes, Van Eyck's paintings are like bodied water colors in oil-- very often like liquid colored glass applied over a careful drawing atop a white gesso ground. I see very little in the way of actually opaque paint, except in the tiniest dots and teensy details. His lighter parts, such as glowing skin and robes, are very thinly painted with the local color, so as to allow the bright gesso ground to shine through.... most everything is a glaze or a translucent veil. By comparison, his darks are often thick-- to hide the light coming from the gesso ground. Much modeling seems to arrive from the density of the applied 'liquid glass' color atop the white gesso ground.[Note: yes, I can sometimes pick out what might be underlying and modeled grisaille work in spots, here and there, in some VE works. I do wonder if these are later additions by other painters not familiar to VE's method...or perhaps VE, himself, made additions to already-completed works by applying a modeling in white and grey before coloring.]

Problem is, when such a 'water-color' technique is performed with straight oils--even thickened oils-- diffusion and spreading soon occur. As such, pigment particles slide around, coalesce in imperfections in the ground; or they diffuse around dust or grit and form noticeable halos; the end result being that nasty stained look-- quite un-appealing to the discerning eye. In noticing this trait, Benjamin R. Haydon wrote in his "Lecture on Art",1844, "Nothing is so hideous, nothing is so detestable as a picture glazed with a thin vehicle which was not prepared for it." Charles Eastlake summed it up in this way: "...for, in proportion as the pigment is thin, the vehicle requires to be substantial." [see "Materials for a History of Painting", 1847, page 504.] I shall add, if the proper medium can be had, history plainly shows that no harm comes from such practice. Sad to relate, this ever-so-effective and desirable practice is generally frowned upon today, owing to the inherent defects coming with use of our currently-available 'state-of-the-art' materials. Returning, I could reasonably suspect Van Eyck must have uncovered an actually innovative 'substantial' medium for performing his wizardry; and that it did not creep or crawl or diffuse itself once applied, and kept its place in the manner of a sort of liquid glass. Whatever it was, it was touted to be quite 'proof against water' (raw or thickened oil and egg are not) and it dried glassy-rich, without requiring any top coat of varnish.

In my own experience, I have found that only a gel or "jelly" vehicle works well with this particular transparent 'water-color' oil painting method.

A vehicle lost

A lost secret? Yes, I do reserve such suspicions. Granted, I wasn't around to look over the brother VE's shoulders, but, whatever their true means to creation, their wonderous works do seem to represent the most perfect transparent technique ever found within the oil painting craft. I am not alone in these 'lost means' thoughts. I do not think the VE's knew their technique and medium would be so durable, for how could they truly know such a thing? But I do think they realized and recognized a good thing when they found it (and utilized it).

It was this new discovery, this liquid glassy medium– a medium so conducive to a rich optical glow and ease in paint-application-- that allowed oil painting to finally capture the easel-painting prize long held by egg tempera. This method and medium simply overwhelmed egg tempera in nearly every way!

The transparent manner of painting never quite died, though it did succumb to a pseudo-opaque method which became increasingly popular during the 1600's. The opaque manner was dependent upon the easy availability of lead white. Lead white allowed texture. Texture allowed another dimension to painted works; and so we find later attempts to combine the opaque in the initial modeling (grisialle) with the transparent in the later stages (glazes, veils) of a multi-layered conjoined opaque-transparent working manner. In so many good hands the effect was certainly wonderful.

Attempts to re-attain the transparent glow did not seem to meet the Van Eyck performance. Several routes were tried to escape or limit the stainy look caused by raw and thickened oil. The use of wax engendered the gel-effect but it did not truly match the prior performance. Ditto wax and resin. Resin and oil in the way of megilp offered some advantage, but I do wonder about total facility in use and its permanency.

I might here mention some known examples to this attempt to recapture the jewel-like 'Van Eyck-ian' performance. Eastlake and others were well-aware of the problem and he did re-introduce the olden oil varnishes– varnishes which provided toughness, durability, and kept the thicker white-derived opaque coloring fresher longer. But, though quite aware of the ‘stainy' deficiencies of oils and varnishes, his writings reveal no discoveries with gel media. The pre-Raphaelite painters attempted to attain the glowing optical quality by use of a wet congealed white lead imprimatur over which were laid the thin transparent colors– a time-consuming tedious affair. Too much pressure on the soft brush and the whole became dull and had to be scrapped off*. Yet, the final effect did achieve the look and is, so far, seemingly quite durable. In the 20th Century, Maxfield Parrish sought the manner by use of three transparent color-layers sandwiched between thinly-applied layers of copal varnish. Too many layers of differing substances! This cannot be good from the standpoint of craftsmanship and longevity. [*For a review of the illuminating Pre-Raphaelite technique, see the "19th C. Copal Varnish" report on our mediums page.]

Is it any wonder that today, we have come full circle; egg tempera is once again regarded as the better method by ever so many practicing painters. Plain and simple, these egg tempera painters are not happy with what has become the standard opaque oil painting methodologies.

Again, whatever it was, this lost manner/medium, a form of easier and more perfect oil painting was the result. It is often noted that oil painting was actually perfected during this particular time frame and much happening within the oil painting realm ever since has been merely a declination. A bit harsh of a sweep, but I can somewhat sympathize with such critique.

Layering and Realism

It would be wonderful if an oil painting could always be created in one even layer. Such a feat would negate most of the effects of poor craftsmanship, as a single layer of paint has instrinsic durability against fissuring, cracking, and other negatives arriving from placing one layer of paint atop another. And so why the need for paint-layers? Simply this: to get it right. To correct, to improve. But how many layers are needed? Unquestionably, the fewest the better! In general, the 1500-1600 Italian system -- such as Titian's manner-- was dependent upon many layers; while the Northern system of the same time-period called for as little beyond one as possible-- and this according to Van Mander's historic writing (see Eastlake's 1st Volume, the chapter headed "The Flemish Technique, Considered Generally) which, for example, is quite characteristic of Rubens' usual method.

Overall, I think most would agree that, technique-wise, rather perfect realism using common opaque oil paint can arrive nicely from a use of three or more paint layers. These three basic layers would be a monochrome, a dead-coloring layer, and a final layer of glazings and veilings with some opaque hightlights. This route is essentially the aforementioned old Italian system. There's leeway, of course. Some might easily forget the monochrome and go directly to an initial colorization; and, beyond the three basic layers would be "heightening" layers applied to further inhance the work by giving additional realism and increased luminosity ( I understand a Van Eyck painting examined by Cormans appeared to have seven actual layers of paint in certain parts. Then again, I also understand, in some cases, additions to VE's works were subsequently applied well after his demise and by other painters hired to "improve" subject matter by the Church ).

By contrast, the Northern method was based upon achieving a final painting in a single and mostly transparent layer. It is quite possible/feasible to paint a marvel all at once, in a single layer, finishing each small section at a time by painting atop a carefully-delineated drawing. If done with a transparent technique over a white gesso ground (sealed, of course), such work would last very well and remain very bright. I cannot say whether Van Eyck always painted in such a single layer. From my own experience I can say it is also easy to believe that at least some additional glazing or veiling and heightening should be performed afterwards to bump effects. Coreman's evidence concerning the Van Eyck he analysed maintains use of multiple layers.... though, again, was this an attempt at subsequent corrective repaintings by Van Eyck.... or something from the later hand of another?

Anyway, I do know that realism builds with layers; and, without a doubt, many other later 'old master' painters did go the layered route. Something should be considered, though. With layers, a fast and firm drying of each paint-application is a valuable asset to such workmanship/craftsmanship. History maintains the Italian 's sunny clime rendered this multi-layered-approach quite feasible by simply placing the painted work out into the sunshine to bone-dry it nicely between coatings. Within the more northern climates, this heat-and-sunning ability would be much less feasible, for the Northern painters had to contend with their colder and wetter realm. Simple oil and pigment paint hates damp and cold! Such conditions warranted a different painting system... and very likely a much different painting medium.to suit.

Along with knowing technique comes the better medium-means to that technique. Oil, by its nature, flows, saturates, spreads. Even standoil does this and in some respects it is worse than raw oil.

Flowing and spreading oil can do things I don't approve of. I want my oil paint to behave itself and stay put where I deem it. I don't want it moving around or slumping after I've taken such care to put it in its proper position-- or its proper shape. Thus, I must also believe the best means to manipulation and painting technique in the landscape is through the use of a gel-type medium; that is, the oil and paint possess the thixotropic nature of a supple jelly. Such a substance can be applied thinly to the ground -- with no eventual running or spreading-- and every brush-stroke and hatching placed upon and into this medium may be, when desired, perfectly retained.

Furthermore, monochrome and paint-layers painted with and into a gel-type medium are microscopically suspended above the white ground, leading to optical effects not attained through the use of non-gelled oils and paint. Such common paint is in no way suspended and thus applied exactly upon the ground or underlying colors. In sum, a certain quality of heightened color and depth is possible with gels which cannot be found through various other means.

As to layering, having a detailed monochrome composition (or, instead, a built-up grisaille) underlying the superimposed paint layers allows realism and often a luminescence which cannot be attained otherwise. Again, for greatest effects the monochrome brush marks must, of course, remain perfectly preserved as intended by the painter-- and this preservation must continue through their drying stage; that is, no melting or spreading and flowing can occur. Further, overpainting must not dissolve this monochrome layer and yet it must stick well to it.

To illustrate this point, imagine you have taken great pains with your monochrome drawing, say, a full and careful delineation of an oak tree ; and its spreading branches deftly described from trunk to smallest tips. After this careful monochrome is dry, it would typically be most valuable to be able to scumble a blue sky across the upper portions of your tree in the dead coloring stage. By such execution, your underlying monochrome oak drawing will show through the blue of the sky to a degree that allows you perfect guidance for completing the final coloration of that oak. To achieve this, your medium that allowed the easy and facile over-scumble of blue paint must not dissolve the careful oak underdrawing (the monochrome). So you see, a certain fast-drying and toughening nature coupled with the barest amount of a solvent (like turps) in the medium is the better means. [ Know that it is also generally understood the 1400-1500 era pre-dated the wide and ready-use of solvents in oil painting....though also do understand certain painters may have still been privy to use of such essential oils.]

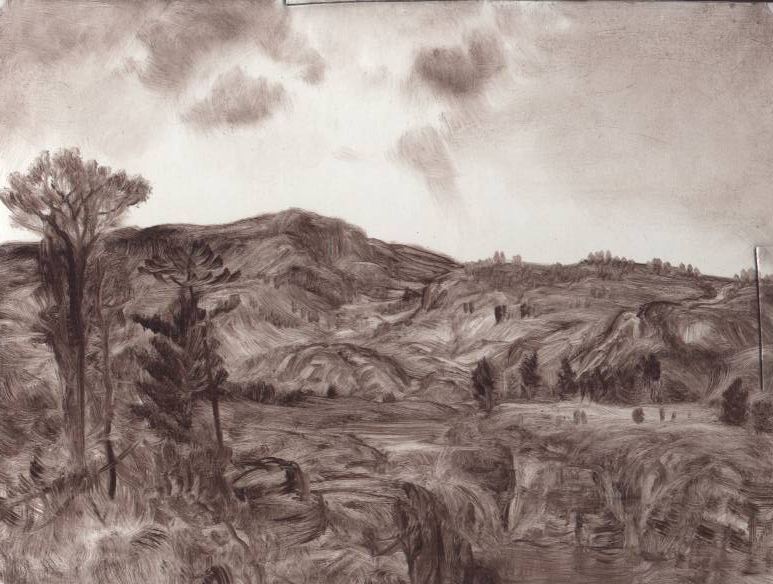

The following work titled "Night Without Darkness" was done in oil using a layered approach beginning with a monochrome scrub-in of thinly-applied lampblack. Once dried this monochrome was glazed over with a predominant local color --this to help establish a close tone and color reference to help my judgement-- and then, immediately while wet, re-inforced with the proper and actual opaque or semi-opaque paint. Once that secondary layer was dried, some further glazing, veiling and heightening was performed. A supple painting jelly made by mixing walnut oil with the Gelling Oil was used from start to finish.

Thixotropic Mediums

Painting mediums run the gamut, being taylored to the preferential working manner of the painter. Those who paint in a mostly opaque manner will find regular oil-and-resin mediums generally quite expedient. But there is another route to great painting, that of the mostly transparent manner. This is a system involving application of the colors atop a white ground in such a way that the white beneath allows a 'stained-glass' richness not attainable through the mostly opaque manner. There are various ways to approach the transparent system-- and various mediums have held favor down through time for such approach. I have found the gelled mediums to be amazing performers with this illusive and illusionary system.

The following image shows the optical and brushing character of yellow ochre, pure, in a straight lean paint applied atop a white non-absorbent ground (A); then with extra oil added (B); and finally the lean ochre with a 50% amount of 'jelly' added(C). This jelly was constructed by adding two parts walnut oil to one part Gelling Oil.

There are differences between the three fully-dried ochre paint samples. Do realize, these optical differences are more noticeable in real life than in this monitor image, which lends transparency where none or little exists.

We can see the 'straight' lean yellow ochre labeled (A) retains the brushstroke hatching but is dull and offers little by way of transparency. In other words, it offers mundane optical refraction; yet this lean paint is espoussed today as being the ticket to great painting.

(B) is visually richer and more glowing in color than (A)owing to the extra oil mixed in. Not excessively oily, the paint remains without running, though oil-diffusion has softened everything-- even the letter "B" has disappeared. Adding some resin-varnish would help allay diffusion, though it will still fall short of a 'jelly'. The extra oil allows easier brushing and finer lines; but we are warned today by many experts to stay away from this oil-rich or medium-rich paint.

(C) shows the advantages of the actual jelly medium, whereby transparency allows the refractive optical glow and marked vivacity. Simple pressure of the brush stroke delivers all values from dark to light merely by dexterity as it slides across the white ground-- everything keeps its intended place w/o diffusion. Notice the letter "C' appears as nearly pure white. This shows the capability for a complete pull-off of the paint from atop the white ground-- a feat often needed in a full-range oil painting technique; and believe me, this is a valuable trait to have in one's arsenal.

Note my use of the word 'vivacity' in the preceding paragraph. The yellow ochre in section C seemingly has more intense color added to it. See how some striations appear as if I have mixed in a somewhat darker, richer orange color; and yet this increased saturation and depth --so unavailable to "A"-- is the result of the glassy gel medium alone, and it arrives via the light from the white ground passing upwards through the suspended pigment. To those today who preach that the basic pigment-and-oil color, as in "A", is all that is necessary to creating stunning wizardry in a painted piece, the superadded glass-like property apparent in "C" plainly proves otherwise, i.e., that the nature of the supplied painting vehicle is of critical importance. [ I am often reminded, while working with transparent painting, how a plant can somehow convert simple brown earth into the brilliant colors of the flower.]

What this illustration shows is that any color mixed with the jelly medium can be utilized for a fast efficient initial modeling of any object -- and without normally needful immediate additions of a light (for highlight),or a dark (for shadow). This extended range of a single color occurs through suspension of the pigment in a sort of liquid glass material-- allowing a brighter inherent optical effect lacking in the noticeably more somber straight paint on the left. Then too, if one wishes smooth gradation, the passing of a soft brush over the whole produces that effect with equal ease. Thus, all advantages are allowed by such a thixotrophic medium; and I can think of no downsides.

Some will argue against ample medium in oil paint today, preferring to starve their pigments of oil; but this simple illustration shows how lean paint lacks the brilliance that comes from adding medium. After all, this refractive brilliance is the strength of painting in oil. The glassy medium allows this brilliance. And, BTW, the richness in effect will increase with paints that are more saturated in color and of darker value. Yellow ochre is a mid-tone paint. Imagine the effect with Venetian red, or ultramarine.

Above: A sketch done with the gelled medium which is one part Gelling Oil and two parts walnut oil. In this multichrome sketch, the clouds are mostly the white of the ground. Likewise, the blue of the sky is transparent, allowing the white ground to light it up from beneath; so, too, are the greys and ochres in the mountain areas. What appears as white modeling in the foothills and rock-topography... is merely the thinned gelled color, pulled back for the light tones; or applied more heavily for the shadowed tones. In such case, the white ground supplies the myriad tones of nature through the pressure of the brush. The use of a firmly-gelled medium incorporated with a shining white ground allows illuminating transparency without causing a 'stainy' appearance. A few highlights of true opaque color, applied here-and-there, provide enough solidity to carry it off perfectly. [Be aware, the camera has recorded the pure white ground as a grey in this image. Compare that grey to the whiteness of the surrounding page and you may get a fair indea of just how bright and glowing this little sketch truly is. BTW, as I noted earlier, regular oil media, when used to transparentize oil paint to such full potential, diffuse and mobilize pigment particles which congregate within imperfections of the ground and around dust in the paint film, causing dark micro-halos and a 'stained' look quite unattractive to the finished appeal of the painted work.]

There are many olden works showing the apparent use of thixotropic mediums. The ability of a thixotropic medium to allow the capture of brush hatchings is well-known. Sampling its historic use, this thixotropic effect is often seen in Ruben's works, leading many today to believe this famous artist used megilp. Another often seen example is the very "wet" or oil-rich looking paint so familiar to Frans Hals' works seems perfectly derived from a gel-type medium. Neither of these well-known masters used what could be termed "dry" paint. On the contrary, the juicy oily media of their choice presents itself to the keen observing eye....and shows no real harm coming by way of painting with an oil-rich medium. But what medium was this? .

Certainly, meguilp is one well-known traditional medium for obtaining a gelling effect. Realize, megilp, by necessity, appears to have come 'into play' only after the widespread introduction of solvents --specifically, turpentine-use-- within oil painting technique. [ Mastic dissolved into turpentine as a picture varnish was a required ingredient of the typical megilp.]

Following right along with the availability of solvents, a thorough historical search will generally show the invention of megilp occurred sometime in the later 1600's-- and it caused a stir. You see, it was believed the lost 'secret of the ages' oil painting additive had once again been found. And ever since then, about every one hundred years or so, the mixing of spirit mastic varnish with leaded drying oil engenders someone of authority to proclaim that, once again, the secret of the old masters has been found ( see my report on Megilp found on the Mediums page, linked at end of this report).

[ This is very curious....it says something about our human nature... and it makes me wonder if another and truly lost jelly medium might have been in actual use for a certain period of time....say, around the mid 1400's through 1500's ...and, perhaps, also still available to Rubens in the early 1600's....? ]

Aside from Megilp, another method for achieving a jelly-like medium is to cook a small amount of wax into it --perhaps an eighth part. Much can be said for this method. Wax is known to have been used by Reynolds and less cracking in the dried paint film results with this substance included in the medium (Yes, I know many of R's paintings are cracked, but those areas containing the wax are amazingly dandy). This is because the wax never truly dries out-- and so the paint stays rather permanently flexible. Additionally, for a number of years afterwards, the wax stops the painting oils from yellowing.

BTW, stand oil also functions in this initial non-yellowing manner. You see, few know this but if the paint never fully dries, the drying yellowing effect inherent to linseed oil will not manifest itself. That is to say, the paint remains light in color. Stand oil is very slow-drying and remains "bright" for many years. However, it does eventually dry and the yellowing is then just as bad as raw linseed oil. It's true. As for the wax, as an ingredient in oil paint, it is, of course, easily dissolved by future cleanings with mild solvents. I have heard no one mention wax as the means to the perfection of oil painting....at least not in the Van Eyck's time frame. Of course, we might presume wax would be easily detected by paint analysis... but maybe not.

Back to Meguilp: it is very popular today, just as it was in the 19th century, and the 18th Century before that. Meguilp has a bad reputation which I believe is mostly due to over-use throughout a painting. In other words, used in proper amounts to the ratio of paint, it seems to work well. Why it allows simple solvent-attack by restorers later on is likely due to its incomplete combination with the oil in the paint. Even though it is microscopically spread about and throughout the paint layer, it is still tiny micro-grains of pure mastic. Thus, the cleaning solvent attacks and returns it to a fluid state. And so the 'bricks' fall apart because the mastic resin 'mortar' is dissolved. Were a clever artist able to figure out how to chemically combine mastic resin into oil to a perfectly clear union, this dissolvability would not be a consideration. You see, once combined with an oil, the resin-in-oil combination is exceedingly tough-- and this is true even when soft resins -- like coniferous types --are used. The old guys were aware of this. I have found formula that direct linseed oil and pine rosin to be heated together ; the resulting varnish being much tougher to the elemental outdoors than either oil or pine resin alone. Somehow, the combination is a blessing to the whole. And so I believe a mastic-in-oil combination is possible and likely quite durable, but, realize, with most high heat-attempts, the gelling effect is almost always compromised. [You see, it takes about 500 degrees F. to truly allow mastic to fully combine with oils. Merely melting mastic resin into oil will not allow the two to chemically combine. Only a cloudy concoction will result below 500+ degrees F, and the actual mastic ingredient will slowly precipitate like micro-snow to the bottom of the bottle. Still, on the side of possibilities, mastic spirit varnish contains turpentine and this solvent may allow some of the mastic resin to actually combine with the oil. I say some because, when freshly-made and used with painting, the turpentine soon evaporates and its ability to 'wed' ingredients is quickly gone from the equation. Perhaps, were the megilp fully made-up and then stored in a bottle/tube for some good aging before use, thanks to the turps involved, the mastic and oil would combine more closely ...?]

BTW, another offshoot from Meguilp are the 19th century Copal-Meguilps. One such medium still in use is known as Roberson's Medium. This particular medium was a Meguilp fortified with hard copal oil varnish, which, not surprisingly, does seem to strengthen it. The 'mortar' is thus made stronger against future cleaning solvent attack. The mastic may still dissolve but the copal 'glue' does not -- thus the weakness of one resin ingredient is somewhat allayed by the strength of the other.

As mentioned slightly above, regarding a layered painting technique, susceptability to harm from overpainting must be considered. Many mediums on the market today contain turpentine or other solvents in substantail amounts. Meguilp is no exception; and, when freshly-made, this jelly contains about 30% turpentine. Just be aware that, when overpainting atop a seemingly dried underpaint (even a well-dried one) the turpentine used in these mediums can dissolve the monochromes and superficially-dried paint-layers. Thus, caution is in great order.

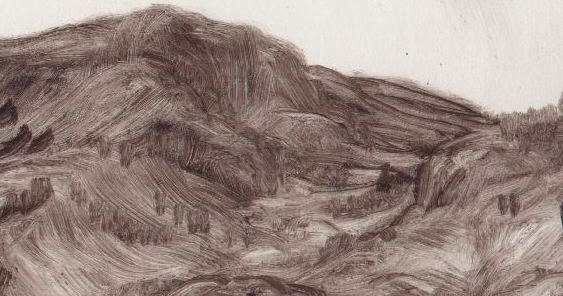

I here provide another 18x24 work produced using painting jelly made with the Gelling Oil. Titled "Sentinel of the North Slope", this work was done in two layers over a very smooth ground of white. The first was a multi-chrome glazed-on underpainting made with thin transparent and varying mixtures of Ult, YO, and Iron oxide red (plus a slight addition of viridian added to the ult for the horizon's light blue area above the distant hill top).

The idea of a multichrome is to state the intended basic colors from the start ; then, when these are dry, proper and true scumbles of opaque color are applied to obviate the stainy effect of the glazed-on underpainting. For instance, in the second layer, an actual blue made from ultramarine plus viridian mixed with lead white was scumbled over the azure area above the hill and gradually darkened in tone by mixing in more ult as the sky extends towards its zenith. This work was initially oiled-out with the painting jelly--very thinly-- so that the glazed-on multichrome effect would keep its place and not run. The resultant and colored dried layer produced allowed very easy over-scumbling/opaque-painting during the second painting. These opaque colors were mixed to a thick-cream consistency and then given a small dose of freshly-made jelly so that they would glide on easily atop the dried multichrome. For more and heightened realism, detail and optical illumination/depth, a third over-painting could be undertaken. [For instance, I could apply a thin blue haze in the distant left hill area to achieve a sense of greater distance. Likewise, greater detail could be added to the clouds and other areas if desired. This heightening ability is the forte of painting in layers -- realism builds with each layer.]

Gelling Oil

The Gelling Oil and the Painting Jelly made there-from does not harm itself by repeated applications; there is minimal solvent action upon the dried paint.

The Gelling Oil is practically colorless and can be made in several ways but we now offer it in an 80 mil. glass bottle. A small amount is extracted from the bottle using, say, the clean palette knife-tip and placed upon a sheet of glass. Afterwards, raw walnut (or linseed oil ) is added and mixed with the gelling oil thoroughly using the knife. The combination produces a light and clear 'jelly' immediately. I then mix in another amount of oil to achieve a softer, more supple gelled painting medium. This soft jelly is then added in slight amounts to handmade paint (about 30-50%). This immixture allows for faster drying and easy facile brushing-- this freeing effect greatly aids the use of small soft brushes necessarily required for detail-work. The paint dries with a wonderful gloss. Not surprisingly, this painting jelly also works very well with commercial tube paint.

[Mixing the Gelling Oil with raw oils is simple and fast. For a visual example, see our next product description for Gelling Copal Varnish, as the process is now the same, excepting the double-addition of oil.]

I prefer to mix the Amber gelling Oil with raw unrefined walnut oil; using a double or eqaul amount of the raw oil. It behaves like a firm or soft painting 'butter'.

Essentially, adding a one or two "drop" amount of the painting jelly is all that is necessary to get the proper consistency with my already hand-ground heavy cream paint. By use of the painting jelly, the paint becomes soft and easily-brushed yet it stands to much better attention and keeps its place where I put it. Again, it does not set up too soon like megilps and exhibit dragging brushwork problems. Yet it usually dries overnight and I am ready to re-paint on the morrow. I also use the painting jelly to lubricate the ground before painting my first and second layers. In subsequent layers, as the tints (glazes, scumbles) are mixed more fluidly with the jelly dominating the mix; there is no real need to oil-out.

The Gelling Oil is aptly named because it gels almost every other oil -- even standoil gels when mixed with the Gelling Oil.. Again, the straight liquid Gelling Oil from the bottle may be mixed with an equal quantity (or, for a softer jelly, double amount) of any other fresh oil (such as Walnut or Linseed) to create a supple painting jelly. If necessary, drying can be further expedited by a placement of the work in direct sunlight for an hour (something about Sunlight causes oils to catalytically begin drying-- even though the work is soon brought indoors again).

By use of the painting jelly, detail is exquisite and super-impositions or corrections are easy -- and dry faster. The open-time for working is perfectly suited to large areas. Due to the ease in overpainting and correctability plus drying, the work is soon ready for the client. [I do not recommend using thick layers of the gel. Lasting qualities and best realism are not to be expected by means of anything other than thin layers of gel, painting jelly, or oil paint containing such. Any gel-layers beyond a slight thickness may stand for awhile but will likely slump over time. Be aware, such thick layers dry slowly and remain undried beneath their dried surface. Any such effects attained for capricious showmanship must be considered poor craftsmanship.]

Once completed, the final work needs no varnish as it will be very glossy of itself. Should a dull spot be encountered, a simple whisper-thin scrubbing of painting jelly is all that is needed to fix the problem.

For a landscape, these are the stages I might recommend to introduce the painter in use of the painting jelly. Portrait painters might do the same but an initial grisaille in monochrome would perhaps better that cause:

a)Monochrome in a single color, usually Black or Black and a Red mixed to a brown. This allows

the setting up of the composition without color. The ground is initially oiled out using painting jelly. Soft or firm brushes are used to paint the monochrome color into this thin gel layer and every hatching of the brush is captured. Detail within this monochrome can be

perfectly accomplished to any degree. Any areas rubbed out by way of correction should be first revitalized by more of the painting jelly.

B) The next day or so, after drying, another layer of painting jelly is brushed out over the monochrome and

colorization begins by first glazing or veiling a local color over the area needing work and

more details painted into this wet color. The monochrome showing through the thin local color

aids the finishing detail. A degree of reality is achieved through this means that cannot be had in

any other way.

C) The work is allowed to dry to a glossy perfection. Or, after drying, further correction and workmanship is undertaken, such as detailing additional tree-branches or applying further haze atmospherics. Generally, it is not necessary to apply any lubrication to help with such details, but rather, a bit more of the jelly than previously required is utilized as an addition to the paint, thinning that paint for perfect ease in applicatiom.

With experience, the painter should progress towards use of a multichrome performance atop a preliminary drawing, whereby the true local colors are directly applied over the white ground by use of the jelly, with no monochrome necessary. Such a multichrome will require little by way of finishing; plus, the illumination from the white ground will show to greatest effect.

Illustrations: This is a small painting done using the painting Jelly as the medium. Though it represents a grand view landscape, it measures only 8 x 11 inches (so as to fit on my small scanner bed).

This is a detail showing how the jelly captures the brush hatchings of the monochrome:

The following image shows the work after the second stage. To demonstrate correctability, I have deleted a foreground tree's upper foliage and, instead, through caprice of slight overpainting, incorporated it into the distant mountainside. Note: I personally would seek a third layer of painting to allow atmospheric haze and illumination in the distance. This is veiling and would help the 3-D illusion of distance receeding from the foreground. Also, to heighten colors, glazings could be simply added atop the existing colors. Again, no further lubrication is necessary, the jelly being increased in the paint make-up instead.

In common with meguilp, Gelling Oil does contain a metallic drier and must be handled with much the same safety and health considerations as Meguilp. It does not contain any balsam, artificial resins, wax, aluminum stearate, or mastic, hydrogenated caster bean oil, or other mechanical gelling agents-- like bentonite or aluminum hydrate. Its formula is not historically-mentioned. As the inventor, I have gone to a great deal of troubles to create it ; thus, like all art material manufacturers today, I keep it to myself. Still, interestingly, the compound could have been made using ingredients readily available to the Van Eycks. These ingredients are known to be very lasting, yet, having invented the Gelling Oil in 1994, I cannot make any statement concerning absolute longevity (contrastingly, in the case of Gentileschi's amber medium, we have the hind-sight of nearly 400 years to gauge results).

Advantages of using the Gelling Oil and its resulting painting jelly:

1. Speeds drying, allowing expediant layering.

2. Provides brilliant optical depth and color effects.

3. Retains brush hatchings aiding preliminary drawing/shading; or development in full multichrome.

4. The painting jelly can be applied thinly as the final perfect coating for the work; when made with raw unrefined walnut oil, it will not develop a 'gallery tone'.

5. The jelly allows perfect rich glazings that stay where placed and remain bright..

6. A small addition renders thick clumsy dragging paint very facile and easy to apply or brush out.

7. The jelly can be used in any amount addition to oil paint ; anywhere from a small percentage addition to 100% total (say, when used as the final coating over sunken areas). However, it is important to always bear in mind, the less pigment and more oil in a paint, the thinner must be the application ; thus, a rich-in-medium glaze (very little color and much medium) should be applied whisper thin, and this to allay the future yellowing of the oil. Tests show the Gelling Oil and resulting painting jelly yellow less than linseed oil. Still, do not over-use these materials or a 'gallery tone' can/may occur.

8. The Gelling oil delivers unique and beneficial oil painting properties, such as the following:

a) When the Gelling Oil is mixed with half itself and raw oil, a polymeric effect resembling stand oil-use results in drying. This effect is similar to what is obtained by adding either stand oil or balsams to oil paint (though there is no stand oil nor balsam in the Gelling Oil). b)This melting effect does not disturb the brush hatchings, and yet it (c)provides, as well, a much more perfect, even, and receptive surface conducive to facile and easy layering additions -- even with soft brushes. No horn-like effect ever occurs.

9. The addition of the jelly strengthens oil paint.

10. Painting jelly dries water clear.

11.Like the other gel-media we offer, full gelation is now immediate when oil is combined with the Amber Gelling Oil.

For those curious, the following is the 1500's story of Van Eyck's 'discovery' of oil painting as written by Georgio Vasari.

"Antonello da Messina, Andrea del Castagno, and Domenico Veneziano" - from Giorgio Vasari's "Lives of the Artists"

From the time of Cimabue pictures either on panel or canvas had been painted in distemper, although the artists felt that a certain softness and freshness was wanting. But although many had sought for some other method, none had succeeded, either by using liquid varnishes, or by mixing the colours in any other way. They could not find any way by which pictures on panels could be made durable like those on the walls, and could be washed without losing the colour. And though many times artists had assembled to discuss the matter, it had been in vain. This same want was felt also by painters out of Italy, in France, Spain, and Germany, and elsewhere. But while matters were in this state John of Bruges, a painter much esteemed in Flanders, set himself to try various kinds of colours and different oils to make varnishes, being one who delighted in alchemy. For having once taken great pains in painting a picture, when he had brought it to a conclusion with great care, he put on the varnish and put it to dry in the sun, as is usual. But either the heat was too great or the wood not seasoned enough, for the panel opened at all the joints. Upon which John, seeing the harm that the heat of the sun had done, determined to do something so that the sun should not spoil any more of his works. And he began to consider whether he could not find a varnish that should dry in the shade without his having to put his pictures in the sun. He made many experiments, and at last found that the oil of linseed and the oil of nuts were the best for drying of all that he tried. Having boiled them with his other mixtures, he made the varnish that he, or rather all the painters of the world, had been so long desiring. He saw that when the colours were mixed with the varnish they acquired a firm consistence, and not only were they safe from injury by water when once they were dry, but the colours seemed to glow and had more lustre without the aid of any varnish, and besides, which seemed more marvellous to him, the colours blended better than in tempera.

The fame of this invention soon spread not only through Flanders, but to Italy and many other parts of the world, and great desire was aroused in other artists to know how he brought his works to such perfection. And seeing his pictures, and not knowing how they were done, finally they were obliged to give him great praise, while at the same time they envied him with a virtuous envy, especially because for a time he would not let any one see him work, or teach any one his secret. But when he was grown old he at last favoured Roger of Bruges, his pupil, with the knowledge, and Roger taught others. But although the merchants bought the paintings and sent them to princes and other great personages to their great profit, the thing was not known beyond Flanders. The pictures, however, especially when they were new, had a strong smell which mixing the medium with colours gives them, so that it would seem the secret might have been discovered; but for many years it was not.

It came about then that some Florentines who traded in Flanders and Naples sent a picture by John containing many figures painted in oil to King Alfonso I of Naples, and the picture pleasing him from the beauty of the figures and the new method of colouring, all the painters in the kingdom came together to see it, and it was highly praised by all.

Now there was a certain Antonello da Messina, a man of an acute mind and well skilled in his art, who had studied drawing at Rome for many years and afterwards worked at Palermo, and came back to Messina his native place, having obtained a good repute for his skill in painting. He, going on business from Sicily to Naples, heard that this picture by John of Bruges had come from Flanders and that it could be washed, and remain perfect. The vivacity of the colours, and the way in which they were blended, had such an effect upon him that, laying aside all other matters, he set off for Flanders. And when he came to Bruges he presented himself to John, and made him many presents of drawings in the Italian manner, and other things, so that John, moved by these and the deference Antonello paid him, and feeling himself growing old, allowed Antonello to see his method of painting in oil, and he did not leave the place until he had learnt all that he desired. But when John was dead Antonello returned to his country to make Italy participate in his useful and convenient secret. And after having spent some months in Messina he went to Venice, where, being a person much given to pleasure, he determined to settle and end is days. T here he painted many pictures in oil, and acquired a great name.

Among the other painters of name who were then in Venice, the chief was a Master Domenico. He received Antonello when he came to Venice with as much attention and courtesy as if he were a very dear friend. Antonello therefore, not to be outdone in courtesy, after a little while taught him the secret of painting in oil. No act of courtesy or kindness could have been more pleasing to him, for it caused him to gain lasting honour in his native place.

Now emulation and honest rivalry are things praiseworthy and to be held in esteem, being necessary and useful to the world; but envy, which cannot endure that another should have praise and honour, deserves the utmost scorn and reproach, as may be seen in the story of the unhappy Andrea dal Castagno, who, great as he was in painting and design, was greater still in the hatred and envy that he bore to other painters, so that the shadow of his sin has hidden the splendour of his talents He was born at a small farm called Castagno, from which he took his surname when he came to live in Florence. Having been left an orphan in his childhood, he was taken by his uncle and employed by him many years in keeping cattle. While at such work it happened one day that to escape the rain he took refuge in a place where one of those country painters who work for little pay was painting a countryman's tabernacle. Andrea, who had never seen anything like it before, excited by curiosity, set himself to watch and to consider the manner of such work, and there awoke within him suddenly such a strong desire and passionate longing for art that without loss of time he began to draw little figures and animals in charcoal, and carve them with the point stones, so as to who saw them. The fame of this new study of Andrea's spread among the country people, and, as fortune would have it, it came to the ears of a Florentine gentleman, named Bernardetto de' Medici, who had land in those parts, and he desired to see the boy. And having heard him talk with much quickness and intelligence, he asked him if he would like to be a painter. And Andrea answering that there was nothing he desired more, he took him with him to Florence, and placed him with one of the masters who were at that time held to be the best. So Andrea, giving himself to study, showed great intelligence in overcoming the difficulties of the art. His colour was somewhat crude, but he was excellent in the movement of figures and in the heads both of men and women. One picture of his which excited the astonishment of artists was a fresco of the Flagellation, which would be the finest of all his works if it had not been so scratched and spoiled by children and simple people, who destroyed the heads and arms of the Jews to avenge, as it were, the injury done to the Lord. ]

Afterwards he was charged to paint a part of the larger chapel of S. Maria Nuova, another part being given to Alesso Baldovinetti, and a third to Domenico da Venezia, who had been brought to Florence on account of his new method of painting in oil. Then Andrea was seized with envy of Domenico, for although he knew himself to be more excellent than he in drawing, yet he could not bear that a foreigner should be caressed and honoured in such a manner by the citizens, and his rage and anger grew so hot that he began to think how he could rid himself of him. Nevertheless, Andrea was as clever in dissimulation as he was in painting, and could assume a cheerful countenance whenever he liked; he was ready in speech, proud, resolute in mind and in every gesture of his body. Being jealous of others as well as of Domenico, he used secretly to scratch their paintings. Even in his youth, if any one found fault with his works, he would let him know by blows or insults that he knew how to defend himself from injury.

But now, resolving to do by treachery what he could not do openly without manifest danger, he feigned great friendship for this Domenico; and he, being a good fellow and amiable, fond of singing and playing the lute, willingly made friends with him, Andrea appearing to be both a man of talent and good company. And this continuing, on one side real and on the other feigned, every night they were found together enjoying themselves, and serenading their loves, which Domenico much delighted in. He also, loving Andrea truly, taught him how to paint in oils, which was not yet known in Tuscany.

Meanwhile, in the chapel of S. Maria Nuova, Andrea painted the Annunciation, which is considered very fine; and on the other side Domenico painted in oils S. Joachim and S. Anna and the birth of our Lady, and below the Betrothal of the Virgin, with a good number of portraits from life: Bernardetto de' Medici, constable of the Florentines, in a red cap, Bernardo Guadagni, the gonfalonier, Folco Portinari, and others of that family. But this work was left unfinished, as will be seen. Andrea, on his side, painted in oils the death of the Virgin, and showed that he knew how to manage oil colours as well as Domenico his rival. In this picture also he put many portraits from life, and in a circle himself like Judas Iscariot, as he was in truth and deed.

Then having brought this work to a successful termination, blinded by envy at the praises he heard given to Domenico, he meditated how to rid himself of him; and having thought of many ways, he at last proceeded in this manner. One evening in summer, Domenico as usual took his lute and departed from S. Maria Nuova, leaving Andrea in his chamber drawing, he having refused to accompany him on the excuse of having to make certain drawings of importance. So Domenico being gone out to his pleasure, Andrea disguised himself and went to wait for him at the corner, and when Domenico came up, returning home, he struck at him with a leaden instrument, and breaking his lute, pierced him in the stomach at the same moment. But thinking he had not done his work as he wished, he struck him on the head heavily, and leaving him on the ground, returned to his room in S. Maria Nuova, and sat down to his drawing as Domenico had left him. In the meantime the servants, having heard a noise, ran out and heard what had happened, and came running to bring the evil tidings to Andrea, the traitor and murderer, whereupon he ran to the place where lay Domenico, and could not be consoled, crying out without ceasing, "Oh, my brother, my brother!" At last Domenico died in his arms, and it could not be found out who it was that had slain him. Nor would it ever have been known, if Andrea on his deathbed had not made confession of the deed.

He lived in honour; but spending much, particularly on his dress and in his manner of living, he left little wealth behind him. When Guiliano de' Medici was slain, and his brother Lorenzo wounded, by the Pazzi and their adherents, the Signory resolved that the conspirators should be painted as traitors on the facade of the palace of the Podesta. And the work being offered to Andrea, he accepted it willingly, being much beholden to the house of Medici. He painted it surprisingly well, and it would be impossible to describe how much art he displayed in the portraits, painted for the most part from the themselves, representing them hanging by feet in all sorts of strange attitudes. The pleased the people so much that from that time he was called no more Andrea dal Castagno, but Andrea degli Impiccati, Andrea of the hanged men. "*

[*Scholars in Eastlake's time, as well as today, question whether the murder ever took place.]

James C. Groves

For Ordering Amber Gelling Varnish online click here

Click here to visit our Gallery page.